Drugs touted by Trump, blood from recovered patients: Seattle scientists seek coronavirus cures

Drugs touted by Trump, blood from recovered patients: Seattle scientists seek coronavirus cures By Sandi Doughton Seattle Times March 30, 2020

Weeks after the fever, sweats and headaches from a nasty bout of COVID-19 were gone, Seattle freelance writer Christy Karras showed up for an appointment at a nearly deserted clinic in South Lake Union. Karras, who doesn’t like needles, averted her eyes as a technician collected 10 vials of her blood.

“I was very proud of myself for being able to fill all the vials,” she said. “I was also proud I didn’t pass out.”

Karras’ blood donation didn’t stem from concern about her own health, but a desire to help find treatments for a disease that has already sickened more than half a million people worldwide and killed 32,000. People like Karras, whose bodies successfully fought off the virus, hold the key to one approach: Harnessing the healing power of the antibodies in their blood.

Researchers around the globe and in Seattle are investigating dozens of other promising ideas, from repurposing old drugs to designing new ones. And they’re doing it at unprecedented speeds.

“This is the most urgent project I have ever been involved in,” said Ruanne Barnabas, a physician and epidemiologist at the University of Washington who’s leading a major study to find out whether hydroxychloroquine — one of the drugs recently touted by President Trump — can protect people from infection. The project was awarded $9.5 million Monday from a $200 million fund created by The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the British government and other donors to accelerate development of COVID-19 treatments.

Seattle scientists are at the vanguard of multiple initiatives to better understand the virus and find ways to fight it. The city was the initial epicenter of the disease in the United States, and the state continues to be a hotspot with 4,896 confirmed cases and 195 deaths as of 11:59 p.m. Saturday. The University of Washington, in particular, was uniquely positioned to respond to the epidemic even before the country’s first case was confirmed in a Snohomish County man.

On that day — Jan. 20 — UW virologist Dr. Helen Chu was at the National Institutes of Health headquarters in Maryland, meeting with Dr. Anthony Fauci and others. The purpose was to discuss the UW’s new status as part of a national network for vaccine and treatment trials, and the looming threat of coronavirus was impossible to ignore.

Chu already had long experience with respiratory diseases, including as part of the Seattle Flu Study. Launched in 2018, the innovative project tracked the spread of flu and other respiratory viruses by sending volunteers home-test kits so they could swab their noses and send the specimens back for analysis.

The study team quickly developed a test for the novel coronavirus but ran afoul of regulators when they began notifying people who tested positive — but who had not consented in advance to the new test. The flu study has since been revamped — with state and federal approval — into a surveillance system called SCAN that is using volunteers and home-test kits to help health officials get a better handle on the virus’ prevalence across King County.

Several groups in Seattle, including Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, are participating in efforts to develop a vaccine against the new virus. But vaccine development will take at least a year — and possibly much longer — and is difficult to speed up. Drugs and treatments could come much sooner, and that’s where many local researchers are focusing their efforts.

Chu is part of a multisite study of remdesivir, an experimental drug developed to treat Ebola. It didn’t work on that disease, but there’s some evidence it might be effective against coronaviruses. With permission from the Food and Drug Administration, doctors at Providence Regional Medical Center in Everett used intravenous remdesivir to treat the first patient hospitalized in the U.S. He improved the next day — but only randomized, controlled clinical trials like Chu’s will be able to provide a definitive answer about the drug’s usefulness.

Half of patients who enroll in the study will get the drug, half will get a placebo. With a goal of 500 patients across the country, Chu thinks the answer will come soon. “I don’t think it will be more than a couple of months.”

Barnabas’ project is also on a fast-track, with results expected this summer. Researchers in Seattle, New York and other cities hope to enroll 2,000 people who have been exposed to the coronavirus — through a sick family member, perhaps — but who haven’t fallen ill themselves. The idea is to dose the volunteers with a 14-day course of hydroxychloroquine tablets — or placebo — and see if it helps them stay healthy.

“More than three-fifths of the transmission occurs within clusters or within households,” Barnabas said. “We want to be able to disrupt that transmission.”

Hydroxychloroquine has long been used to treat malaria and is so safe — at proper doses — that people up to 80 years old can enroll in the trials, Barnabas said. Some recent test tube experiments and results from Chinese COVID-19 patients hint that the drug and its close relative chloroquine might prevent the virus from invading lung cells. But people have been poisoned, and at least one man died, after dosing themselves with dangerously high amounts of the drugs or similar, but toxic, chemicals.

Many other existing medications, already approved for use against conditions ranging from cancer and tapeworms to gout and psychosis, also hold the potential to fight the new coronavirus — and could be rolled out much more quickly than new treatments, said UW virologist Stephen Polyak. He’s been working for years to find ways to repurpose and combine some of those compounds, with the goal of creating antiviral “cocktails” that could be stockpiled and deployed as first-line treatments when new diseases emerge.

“It took a pandemic for my research to become relevant,” he said.

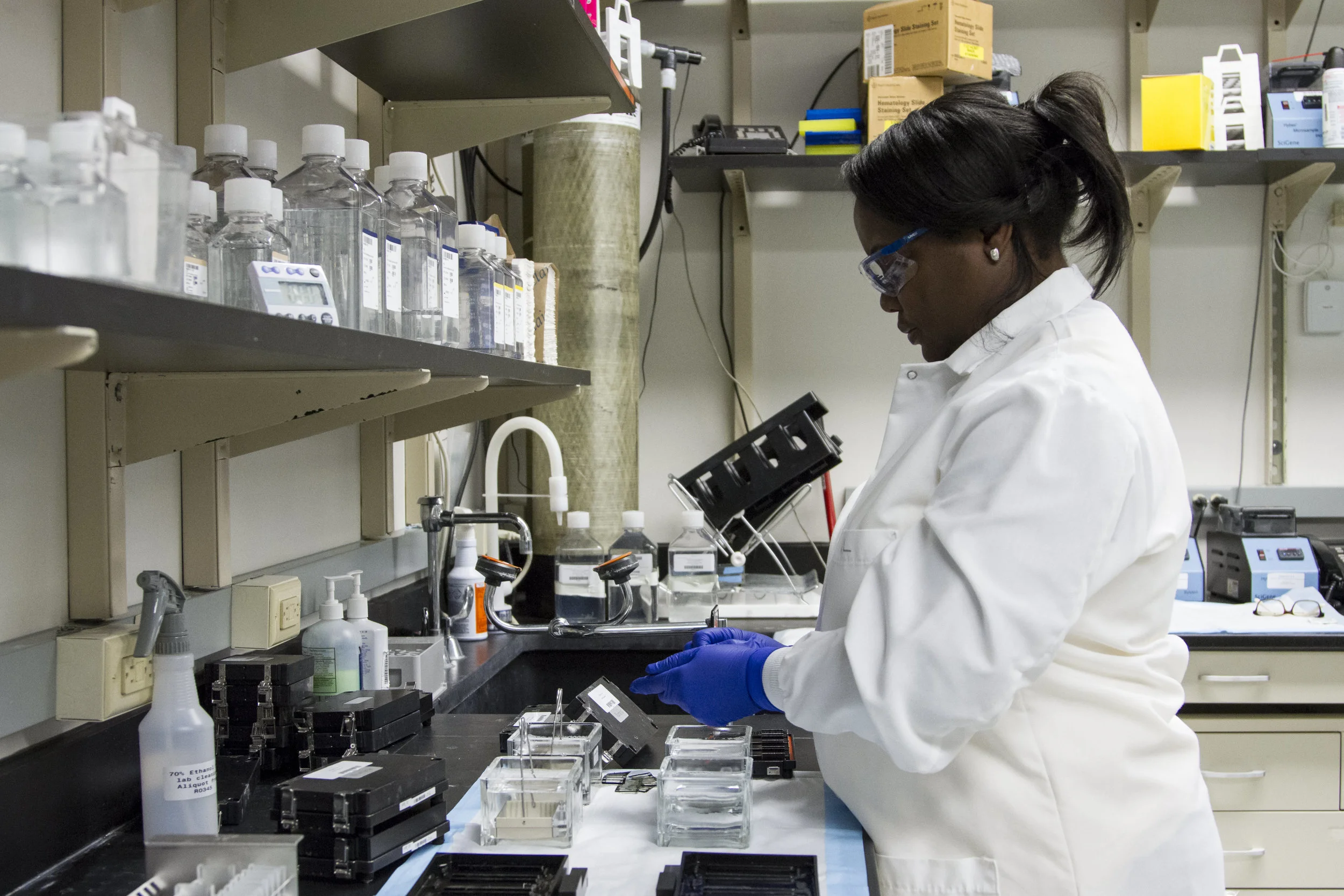

With $40,000 in initial funding from the Washington Research Foundation, Polyak and his colleagues are setting up a system to screen multiple drugs and combinations for their ability to thwart the new coronavirus at different points in its infectious pathway. Federal funding agencies have been moving quickly to provide money for studies and make it easier to test possible treatments, and Polyak is hoping he will be able to scale up his project to bring potential treatments closer to clinical use.

“My dream would be to do a combination study here in Seattle,” he said.

Chu also quickly pivoted another of her research projects to focus on the new coronavirus. She’s analyzing nasal swabs and blood samples from people with COVID-19 to map out their immune responses. About 20 patients have volunteered so far, most of whom were extremely ill and under strict quarantine. Chu and her colleagues had to use elaborate safeguards to get consent forms, enlisting nurses in protective gear to present the documents to the patients, then hold the signed forms up to the window for the researchers to photograph.

Chu said she’s been surprised by how many patients are in their 30s, 40s and 50s. “This disease seems to be causing young people to get sick, and to get sick very quickly,” she said. “And it’s also causing the older people to get sick and the speed of decline can be very fast.”

Many of the volunteers got better, but some did not. Chu, who eventually wants to include 200 people in the study, is trying to understand the difference between those who live and those who die, and what a successful immune response looks like.

People who recover do so largely because their bodies produce disease-fighting proteins called antibodies in sufficient amounts and types to neutralize the immediate threat posed by the virus. Their immune systems are also primed to recognize and attack the virus the next time it appears. “Your body adapts, and the cells of your immune system change so they can fight off the infection more readily when they see it again,” said Marion Pepper, a UW immunologist who is launching a COVID-19 antibody study.

The most direct way to leverage antibodies to help critically ill patients is through infusions of donor plasma, the clear, antibody-rich liquid that remains after red blood cells are removed. The approach dates back to the early 1900s when it was used with varying success against measles, polio, mumps and influenza. It was also used sparingly during the 2014 Ebola epidemic. Physicians in New York recently got emergency permission to begin treating COVID-19 patients with “convalescent plasma” and hope to begin as soon as this week.

Chu, Pepper and other Seattle scientists are taking a different tack in working with blood from recovered patients. By isolating the immune system cells programmed to recognize and pump out antibodies against the novel coronavirus, they hope to mass-produce those antibodies and turn them into treatments.

It’s an approach that didn’t work well against Ebola but has been successful in protecting babies against a type of viral pneumonia, Chu said.

It’s important to have multiple groups tackling the virus from different angles, said Dr. Larry Corey, virologist and president emeritus of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, who’s collaborating with Chu. “The Seattle science community is taking a rapid interest and pursuing a diversity of ideas and it’s terrific,” he said. “You can’t always anticipate which way the science is going to go.”

The epidemic is also inspiring new ways of doing science.

For Barnabas’ hydroxychloroquine study, volunteers will never have to visit a clinic. Their initial interview will be via videoconference. The medication will be delivered to their homes, along with two weeks’ worth of nasal swabs, which will be picked up daily for analysis.

In addition to collecting samples from hospitalized patients, researchers at Seattle’s Institute for Systems Biology plan to deploy mobile phlebotomy labs to collect blood from infected volunteers who are self-treating at home. They also plan to leverage the institute’s experience with enormous databases to analyze the samples at a level of detail few labs can match, including full genetic sequences for some patients to help identify potential risk factors for the disease.

“We’ll be collecting a few gigabytes per patient,” said Jim Heath, ISB president.

Karras, who wrote about her experience with COVID-19 for The Seattle Times, stands ready to donate blood again — and again, to help the efforts.

“I hope anybody who wants my antibodies will ask for them,” she said. “I’m ready to give more whenever they want it.”